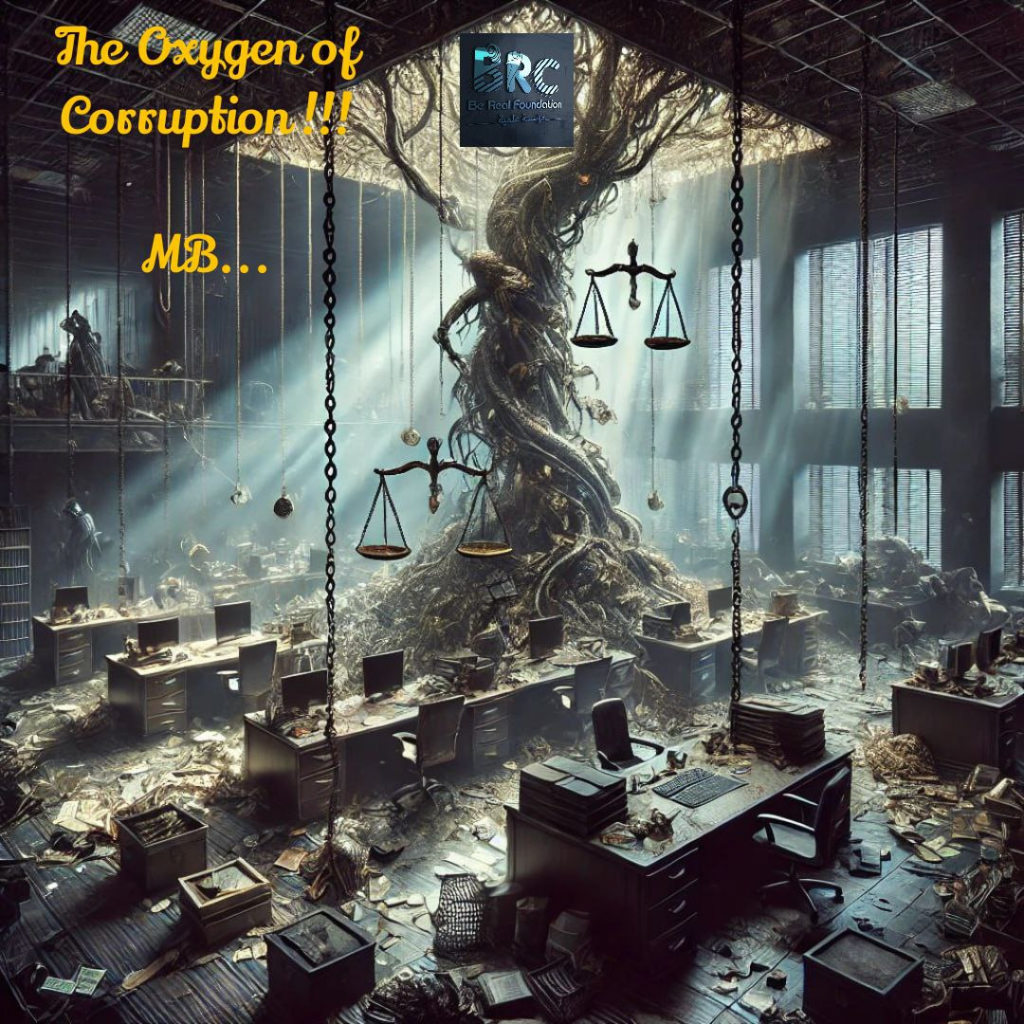

The Oxygen of Corruption !!!

By Dr. Methaq Bayyat Al-Dhafei…

Corruption thus is not only an ethical, economic, and political problem but also a theoretical and real social problem. More strictly speaking, corruption is a modern problem of society. What may be elicited from our notions about it? When we observe corruption prevailing, the following ought to be considered on each side: corruption as a practice in social influence, and corruption as a subject to talk about in society and its members with respect to one another. Corruption gives populist anger, fuels indifference and separation from politics, and speeds up deep, political modifications. Being an evidence of backwardness, corruption is said to touch upon some collective sense of justice and trust, though at the same time it is a source of feelings that if a person makes an effort to fight it, then the situation can change. Besides, it is still worth explaining the ways in which corruption is being revived nowadays and almost everywhere, for it is nothing but a form of realization of individualistic wishes in a society in which its members do not trust one another and do not control their actions.

We fail to always notice the structural requirements of corruption and the role of institutions and their impact. The roles of these mediating cases—rebuilding of psychological processes and individual choices—do not answer the question of the benefit considerations, interests, and contradictions of the value in society that lead to the reality of participation in a corrupt “network” that becomes useful and demanded behavior. People who see corruption from the outside claim that its level of spread represents a crisis of the public structures for the maintenance of law and order, which is expressed not only in the deviation of particular actors from social norms but first of all in the wrong distribution of public goods like money, power, reputation, and moral authority.

Integrating the “moral” aspect into corruption as an expression of actors’ moral inferiority seems to me unproductive and ineffective—we are not in the age of prophets! This kind of classification hides the contradictory nature of the normative system of a society, which allows a dual situation to arise, giving actors the basis to blur the boundaries between corruption and non-corruption at the individual level. If actors have reasons to replace the distinction between categories of moral and immoral behavior with categories of success and failure, blurring these boundaries is a response to real or imagined external pressure, placing individuals in a dilemma of whether to participate in corruption or not.

The theoretical assumptions are reduced to be activated in a referential analysis of the conditions in which an act of corruption occurs. Typically, the motives do not exceed previously established justifications. The search for a specific personality type prone to behavioral distortion always ends in failure. The stereotype of a “corrupt personality” helps maintain existing structures, provides psychological comfort, and ensures its detection and identification. There is no doubt that corruption offers individual benefits and aligns with a model of reciprocal benefit for some, conducted at the expense of third parties, protected by actors actively working to conceal the arrangement.

It is clear that personality traits alone cannot be the sole criterion for distinguishing between a corrupt politician or businessman and a respected or self-serving professional. The theory of corruption choices and declarations returns to the circumstances in which an individual finds themselves and the motivations and stimuli generated by specific corruption cases. However, analyzing possibilities does not replace answering the question of which areas of social development allow old mechanisms to persist in modern times or why new conditions and incentives create opportunities not only for corruption but also for moral and political opposition to it.

Reducing the issue to distinguishing between state failure and market failure overly simplifies the matter. Depending on ideological preferences, society can be organized as either a market or an ideal democratic state to suffocate the oxygen of corruption. It is not enough for the theory of fragile democracy to assume that corruption is a functional element of authoritarian systems. Undoubtedly, centralized regimes provide more opportunities for personal gain in the absence of competition or public oversight. Thus, the debate continues on whether a strong state is prone to corruption due to its strength or because it fails to generate trust in its institutions’ legitimacy and effectiveness, making it vulnerable to elite political and economic corruption.

Corruption functions as a substitute for the absence of institutional legitimacy and effectiveness or the inability to involve certain social groups. Understanding the conditions and incentives for corruption and identifying the logic behind corrupt actors’ decisions is crucial. Power and money intertwine subtly—money facilitates power, and power opens new opportunities for money. Is there a better way to reinforce friendship than this? The old adage rings true: “Small bribes sustain friendships, but large bribes make them predictable.”

One can find similar reflections, but they are argued in broader terms regarding the uneven development of public life sectors, which lack unified standards of accountability and integrity. Traditional forms of gift-giving, nepotism, and favoritism persist. Existing structures in organizations and administrative bodies rarely meet standards of public interest protection, instead being part of a binding network of giving and receiving.

From a realistic perspective, one might argue that corruption is a functional phenomenon, while morality, in this case, conflicts with the “realism” that allows everything to take its course. Historical case analyses confirm that corruption has a pervasive economic, political, and social impact. It deepens poverty, obstructs social mobility, hinders economic growth, and transforms political systems into failures, ultimately undermining their legitimacy. Corruption is presented as a return to primitive exchanges and lowly relationships, encompassing direct political action and its corresponding economic consequences.

Corruption will continue to develop wherever there is no authority to govern the political system. Global and impersonal standards for government or political figures’ operations have not yet succeeded in overcoming individuals’ personal interests. The same applies to cases where income, power, or prestige distribution relies on false standards, social class, or other fabricated criteria. Social inequality, stemming from stratification, leads actors—individuals or groups—to pay for the desired aristocratic status or exploit corruption to make self-enriching decisions.

In all societies, nothing undermines individuals’ confidence that they deserve more than what they have or that others’ success results from unfair competition. Consequently, the value systems of societies—with their false focus on achieving equality and expressing freedom of will—can never truly satisfy their populations. This dissatisfaction, compounded by economic extremism, systemic corruption, and the brutality of political institutions, leaves people perpetually discontent.